“The timber supply for the next few decades is already in the ground.”

Relative to softwood, the amount of available useful hardwood will remain small, but it will grow significantly from current levels. There are opportunities here to make better use of species such as sycamore, beech and birch – although the amount considered suitable for traditional products will be severely limited. Perhaps this use can be in the form of engineered and modified wood products, and manufacturing streams that can deal with a wider range of wood – including the increasingly important resource of recycled and recovered wood. Wood fuel has an uncertain future, thanks to concerns over air quality and the rise of ever more effective renewable alternatives. There is perhaps more of a future in the form of wood-based liquid fuels in the longer term.

Climate change impacts are also coming quickly. In the UK, we can expect more summer drought and periods of more intense rainfall. Trees will have to cope with feast-famine cycles for water, with risks to wood quality as well as tree health. In this horizon, we can also expect more market disturbances. We can try to reduce the risk of forest fire, storm damage, pest and diseases in our own country, but since the timber trade is global, there will be more feast-famine cycles for the wood supply – large volumes reaching markets as a result of disasters, and shortages and demand pull from other parts of the world. We also know the enormous effect politics can have and should not forget how much of the global forest resource is controlled by single countries. Trying to move our value chains to a more diverse diet of wood will help mitigate the risk.

During this period, we will see a growing wood hunger. Efforts to use wood in the place of more carbon intensive materials will continue. There are also some basic, high volume, trends – such as the increasing demand for tissue as global living quality increases, and the growing need for textiles (never mind the need to produce a higher proportion from wood-based fibre instead of fossil-based synthetics and water hungry cotton). There is also hunger in the literal sense, with the use of wood derivatives in food.

Despite restrictions on combustible building materials, the use of sawn timber and board products in construction will grow, but there will be gradual changes in the type of construction work, with more emphasis on renovation and retrofit of existing buildings, and design for disassembly and reuse in new ones. Perhaps technology will allow an economically viable shift back towards local supply chains and customisation, providing a niche for homegrown material against the backdrop of imports that we have no option but to rely on to satisfy the majority of the demand.

For the second horizon, resilience has been the watchword, encouraging us to plan ahead for forests that are diverse enough in species, genetics, age and structure, to be able to recover from disturbances. But we should not talk just about resilient forests, but also of resilient value chains – also robust enough to cope with disturbances, and adapt to changes in the natural, social, and economic environment. Value chains that rely on a consistent supply of a small number of species and narrow quality requirements will be exposed to ever-increasing risk. Fortunately, scientific developments ongoing now, such as new materials from cellulose, lignin hemicellulose and extractives, will come to the industrial stage in this horizon.

We are likely to see more forests being reserved for protection areas, perhaps offering income from recreation and tourism, but not able to provide much to satisfy the ever-growing wood demand. This means we will be expecting more from production forests, managed in intensive but resilient ways we have yet to figure out, but benefiting from new sciences such as genomics to accelerate tree improvement. It is impossible to say exactly what uses forest products will be put to several decades from now, in a world that will surely be very different. But experience has shown that trees, grown with no purpose in mind, do not lend themselves to high value products.

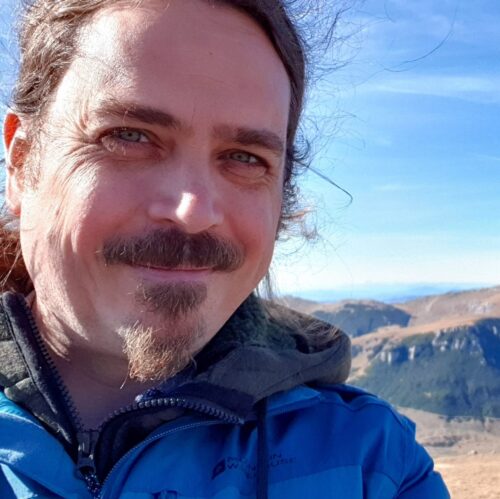

Dan Ridley-Ellis is head of the Centre Wood Science and Technology at Edinburgh Napier University.

He is one of the UK’s technical experts on guessing the strength of wood and can talk for hours on the topic – which he frequently does if nobody stops him. His main area of research is understanding the properties of wood, and how they are influenced by tree growth, forest management, and climate. His most recent work has been focusing on the potential of lesser used, and lesser known, species, and preparing for the wood value chain of the future.

He represents the UK at European Standards Committees for grading of construction timber, and the majority of structural sawn timber produced in the UK is now graded with settings he developed. He is also active in online learning, public engagement and science communication. He is the lead organiser of Bright Club Edinburgh, where researchers do stand-up comedy.