A blog by Southern England Assistant Forest Manager Rob Coltman

Hello and a belated Happy New Year!

For many of us, the festive season will have faded in to a distant memory, as we wade out to work in rainy mid-winter. However, I’m currently feeling fortunate, I had some respite from our climate in the form of an amazing three week trip to New Zealand. For anyone who is feeling the strain following the return after Christmas, my heart goes out to you. I only hope you can take some solace in the fact that I’ve already used most of my holiday allowance for the year and have a long slog ahead.

An exploration of New Zealand from the perspective of a forester is intoxicating. It is such a joy to experience their native forests – southern beech’s coated in mosses and lichens; enormous tree ferns over 15 metres tall; Pōhutukawa trees resplendent with red flowers; the mighty Totara tree towering over the canopy; native palms, manuka (and the associated honey), and of course the iconic Kauri tree. These species have evolved so far from our native British tree families, making a walk through a New Zealand forest an exciting and exotic encounter.

There are of course some familiar specimens, most notably the Monterey pine (Pinus radiata). About 7% of New Zealand’s land mass is plantation forestry and radiata pine makes up 90% of that stock. The remainder is made up of 6% Douglas fir, Eucalyptus, and a few native species. Harvesting of native trees is limited in New Zealand on account of massive historic overcutting of ancient virgin forests – a similar story to what happened to the California redwoods. Using improved stock, the Kiwi’s are able to grow Monterey pine in staggering 27-year rotations. In the 1920’s the Kaingaroa Forest was planted. The forest consists mostly of radiata pine and covers an area of 2900 km². At the time of planting, it was the world’s largest plantation forest. The New Zealand forestry industry contributes £2.5 billion to their economy, employs over 20,000 people and forms 3% of the country’s GDP. Forestry in New Zealand is, in short, a big deal.

I’d like to be able to comment more on New Zealand forestry, however I am in a state of permanent regret for arriving at the Timber Museum five minutes after closing and consequently my knowledge is more limited than I’d like it to be! Instead, I’ll move on to the main subject I’d like to discuss in this blog, that of biosecurity.

The link between biosecurity and me shoehorning my holiday in to the blog comes via the Kauri tree – Agathis australis. The species is from the Araucariaceae family, an ancient family of conifers that also contains the monkey puzzle (Araucaria araucana). The Kauri tree has a history going back over 135 million years but has had a rough time of it in the last 200. The species has been hit on two fronts – initially from around 1820 when European settlers began to harvest the huge trees that covered the north island of the country. The timber is hard and the large dimensions present in these massive trees made it ideal for construction and boat building. Continued harvesting over the next 150 years reduced the natural range of the species to 4% of its original size. Then, in the 1970’s a new pathogen – Phytophthora agathidicida – was discovered affecting the Kauri. Since discovery, the range of P. agathidicida has expanded rapidly, infecting Kauri trees across the country. The rapidity of its spread suggests the disease was introduced to New Zealand by human activity. An infection of P. agathidicida on Kauri almost always leads to the death of the tree.

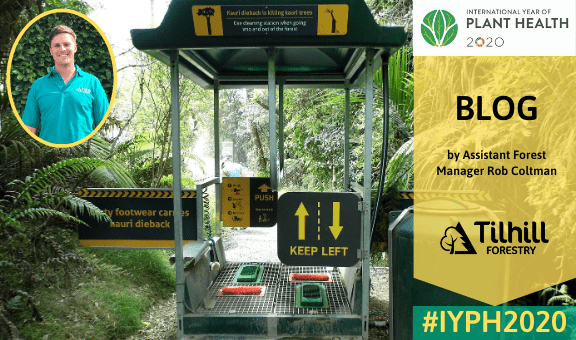

The New Zealand Department of Conservation have tried to stem the infection rate between forests. I saw some really excellent biosecurity measures in place at trail entrances (see picture below), offering people the opportunity to scrub mud from boots and walk through gates that sprayed anti-fungal mist on to the bottom of the shoes. In many locations there are strict rules around leaving the path and staying off the roots of trees. This has been cleverly achieved in some locations with high visitor numbers by building decking that raises above the roots, still allowing you close access to the huge trunks of some individual Kauri’s.

I found this all very impressive, though I understand how the loss of a dear and iconic species can focus the mind to scientific research and creative solutions. The loss of ash in the UK never gets any easier to consider, though there have been promising projects going on in selecting some specimens which show some resistance to Chalara, as reported by Tilhill Forestry. In addition to this, it has been suggested that the genetics of native UK ash trees make them more resilient to emerald ash borer. Reasons to be cheerful, I hope.

Ultimately, it would be ideal if we could avoid introduced pests and diseases altogether and reduce the spread of existing ones. This is undoubtably a mammoth task in a globalised world with people and products moving across ecological borders all the time. There’s a well-versed debate about the value of internationally traded plant material and I’m going to sidestep that one on this occasion. Instead, I’m going to focus on things that I have some influence over as a forest manager and what better format to use than the good old New Year’s Resolution?

In 2020, I intend to:

- Clean boots – all the time!

I do try my best to stay on top of my boot regime, cleaning and spraying the disinfectant Propellar whenever moving between sites. However, there is always room for improvement. - Research existing UK pests and diseases.

I was lucky at university to get a good review of UK forestry pests and diseases, though I do still regularly need to do a bit of research to refresh myself – there’s so many out there to keep on top of unfortunately. - Review what pathogens may be expected to enter the UK in the future.

I’m based in the south east of England and we are potentially in the firing line for pests and pathogens coming across the Channel. This was made clear to me in 2019 when Ips typographus (larger eight-toothed European spruce bark beetle) was discovered close to one of our sites and suspected to have flown across from the continent. - Communicate the risks of pests and disease to contractors.

No one sees more of the woods than those who are on the ground. If we all know what to look out for, there’s a greater potential to mitigate the spread or impact an invasive pests or diseases.

If you do come across any trees in poor health, consider reporting it to TreeAlert. The page allows anyone to inform Forest Research about the health of their local trees and feeds in to a growing pool of information to help better protect the nation’s forest resource. It’s quite easy to use and there’s plenty of info on the page to help identify the pest or disease you might be looking at.

I sincerely hope that we can work towards a future with a lower biosecurity risk. Good tree health is essential to our forests and forest industry. The ramifications of timber security run alongside that of food security. The importance of the issue is being publicised by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) by making 2020 the “International Year of Plant Health”. The solutions are as complex and multifaceted as the globalised economy, but we must do our bit to try and help. As foresters, we’ve a responsibility to protect our forests now and for future generations. I believe that proper biosecurity measures are an essential part of that protection and ultimately, good forestry practice.

Promote the International Year of Plant Health using the hashtag: #IYPH2020